What Is The Halo Effect?

The halo effect is one of the best known cognitive biases in psychology and one that we can frequently observe in everyday life. This term was coined in 1920 by the psychologist Edward L. Thorndike from his investigations with the army, when he observed that the officers attributed a positive assessment to them, often starting from a single characteristic, a single observed trait. Or on the contrary, they attributed negative general characteristics when they saw in their superiors a not so adequate quality at a given moment.

The halo effect consists of making an erroneous generalization based on a single characteristic or quality of an object or a person. That is, we carry out a preliminary judgment from which we generalize the rest of the characteristics. If we think about it, this type of bias is something that we apply very often almost without realizing it. We do it when we see, for example, someone attractive and we assume (unconsciously) that their personality will also be just as pleasant.

However, the beautiful is not always good, not a single feature is enough to draw a general and absolute idea about a person or dimension. The halo effect leads us to infer characteristics from very little information, that is , we presuppose, value and even conclude certain data without knowing how dangerous something like this can sometimes be.

The halo effect in everyday life

Daniel Kahneman is a renowned psychologist who worked and studied in detail the phenomenon of the halo effect. Thus, in his book “Think fast, think slowly” he points out how this bias is part of any area of our life. For example, if someone is very handsome or attractive, we attribute another series of positive characteristics to them without having checked whether they have them or not, such as being intelligent, seductive or pleasant. Or, on the contrary, if someone seems ugly to us, we can think that they will be a boring and unfriendly person.

Furthermore, according to Professor Kahneman, teachers also have their favorite students. Those who tend to get better grades are treated more benevolently on average than those who have more difficulties or do worse. This fact is so evident that many universities have established, for example, measures to prevent the halo effect.

One of them is the University of New England, in Australia, where they conducted a study to see if the students’ grades by their teachers were mediated or not by this cognitive bias. Today they have adequate strategies so that the valuation is always as neutral as possible. All of this forces us to conclude with a very simple fact. People make value judgments on a regular basis.

We do that yes, without the bad intention. We do not seek to label or judge lightly but we do so for a fact that we are not always aware of: our brain needs to get a quick idea about what surrounds it. You want to know who or what you can trust, who offers you security and what is better to keep your distance. Hence a single characteristic often suffices to make a general (and often misleading) inference.

Likewise, we can observe the halo effect when we know what a person does in their work, categorizing it according to whether they are a doctor, carpenter or receptionist. Even in marketing, this technique is widely used as a strategy to improve the image of some products and better position a brand in the market.

We can also be aware of the halo effect in job interviews , referring to the bias that an interviewer, when seeing a positive trait in the interviewee, ignores the negative traits or pays them less attention, or vice versa.

The Nisbett and Willson experiments

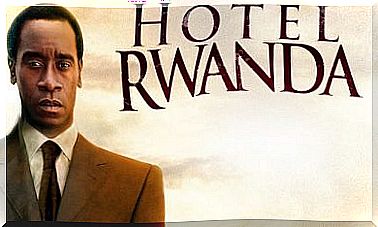

Nisbett and Willson subsequently conducted an experiment on Thorndike at the University of Michigan with two groups of students (118 in all). Each group was shown a video of a teacher in class, the same for both groups.

He differed in his behavior, in one of the videos the teacher was cordial and affable, and in the other he was authoritative and imperative. That is, in one video the teacher was shown with positive qualities and in another with negative qualities. Subsequently, each of the groups was asked to describe the physical appearance of the teacher. And here is where the most curious thing about this experiment comes from.

The results of the experiment

Those students who saw the positive side of the teacher described him as a nice and attractive person. Meanwhile, those who observed the negative side rated it with unflattering adjectives. But the matter went further, since the students were then asked if they thought that the teacher’s attitude could have influenced their evaluation of physical appearance, all of them answering with a resounding “no”, and arguing that their judgments were totally objectives.

In short, this reflects the reality of the halo effect and how little we know about what influences our assessment of people and our environment. This is because although we believe that we make objective judgments, they may not be so, perhaps supporting that statement that we often hear that the first impression is what counts. Even so, this phenomenon does not always happen, in other situations some variables such as context or affect can also exert some influence.

Image courtesy of f_antolin