The Psychological Writings Of John Stuart Mill

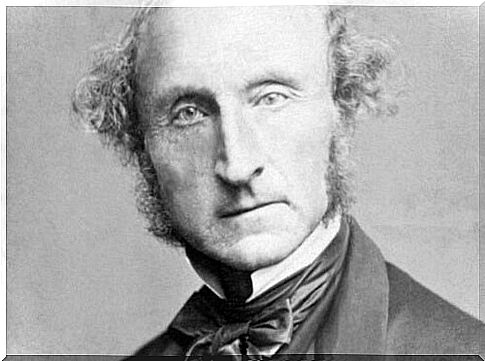

John Stuart Mill (1806 -1873) was an English philosopher, politician and economist representative of the classical economic and theoretical school of utilitarianism. This ethical approach is proposed by his godfather Jeremy Bentham. Mill profoundly influenced the form of British political thought and discourse in the 19th century.

The doctrine of utilitarianism defended by John Stuart Mill accepts the utility or principle of maximum happiness as the foundation of morality.

It maintains that the actions are correct in proportion to its tendency to promote happiness. They would be wrong if they tend to produce the opposite of happiness. By happiness we mean pleasure and the absence of pain, by unhappiness pain and the deprivation of pleasure.

It also defends that the only reason for which power of attorney can justify harm caused to third parties is to avoid harm to others. Regarding the subjection of women, he compares the legal situation of women with the condition of slaves and defends equality in marriage and the law.

Life of John Stuart Mill

Young John Stuart Mill was seen as the heir to the radical philosophical movement and his famous upbringing reflected the hopes of his father and Jeremy Bentham.

Under the dominating gaze of his father, they taught him Greek at the age of three and Latin at the age of eight. He studied logic and mathematics, went on to political economy and legal philosophy in his teens, and later to metaphysics.

The strictness of his education was probably one of the factors that precipitated his “mental crisis” of 1826. There have been a wide variety of attempts to explain what led to this crisis.

Most focus on the relationship with his father. More important is the crisis that represents the beginning of John Stuart Mill’s struggle to revise the thinking of his father and Bentham.

Struggle to overcome depression

Mill claims that he began to come out of his depression with the help of poetry, specifically Wordsworth’s. This way out of his particular well made him think that while his education had furthered his analytical skills, it had negated other abilities.

John Stuart Mill chose to represent a parliamentary seat. Although he was not particularly effective during his tenure as a deputy, he participated in key events.

He tried to amend the Reform Act of 1867 to substitute “person” for “man” so that the franchise would be extended to women. Though the effort failed, it fueled the tide that would lead to women’s suffrage.

After his term in Parliament ended and he was not re-elected, he began spending more time in France living with his wife’s daughter, Helen Taylor. It was to her that he pronounced his last words in 1873: ” You know I have done my job .” He was buried alongside his wife, Harriet.

Psychological Writings of John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill’s commitment to methodological individualism makes psychology the fundamental moral science. He distinguishes between a posteriori and a priori schools of psychology. The first ” resolves the entire content of the mind in experience .”

In the a priori or intuitionist school, the experience ” is itself a product of the mind’s own forces that work on the impressions we receive from outside and always has a mental and external element “.

Association theory

The associationist version of a posteriori psychology has two basic doctrines:

- First, the most recondite phenomena of the mind are formed from the simplest and most elemental.

- The second is that the mental law that makes this formation possible is the law of association.

Association psychologists would try to explain mental phenomena, understanding them as the interaction of simpler components derived from experience (for example, color, sound, smell, pleasure, pain). Elements that would end up connecting with each other to give rise to the associations with which we work on a mental level.

These associations take two basic forms: similarity and contiguity in space and / or time. Therefore, these psychologists try to explain our idea of an orange or our feelings of greed as the product of simpler ideas connected by association.

Part of the impetus for this explanation of psychology is its apparent scientific character and beauty. Associationism attempts to explain a great variety of mental phenomena on the basis of experience and very few mental laws of association.

Thus, it appeals to those who are particularly drawn to simplicity in its scientific theories.

Moral education and social reform from associationism

Yet another attraction of association psychology is its implications for views on moral education and social reform.

The contents of our minds, including moral beliefs and feelings, are products of experiences that we experience connected according to very simple laws. This raises the possibility that human beings are capable of being radically reformed.

In other words, accepting the hypothesis that our minds are linked by laws of association that work on the materials of experience, we would come to a singular conclusion: if our experiences change, so does our mind. This doctrine focuses on social and political institutions such as the family, the workplace, and the state.

Therefore, associationism fits perfectly into a reform agenda because it suggests that many of the problems of individuals are explained by their situations (and the associations that promote these situations) rather than by some intrinsic characteristic of the mind.

conclusion

Today, despite the years and social and economic transcendent changes since his death, the writings of John Stuart Mill continue to be a reference. Many of his texts, particularly on freedom, utilitarianism, the submission of women and his autobiography defend ideas or address debates that have not left the present time.

Mill’s intellect became involved with the world instead of running from it. His was not an ivory tower philosophy, even when it came to the most abstract of philosophical subjects.

His work is of permanent interest because it reflects how an intelligent and prepared mind struggled and tried to bring together the best of different intellectual and cultural endeavors.

Thus, Mill’s thought is at the intersection of the conflicts between enlightenment and romanticism, liberalism and conservatism, and historicism and rationalism.