Karoshi: Death From Overwork

On Christmas Day 2015, Matsuri Takahashi, a 24-year-old woman, threw herself out of the window of her home. He had started working at Dentsu, the global advertising giant, in April of the same year. One more victim of Karoshi , the ‘death due to overwork’, recognized as an occupational accident since 1989 by the Japanese authorities.

On his Twitter account, Matsuri had admitted that he only slept “two hours” a day and that he worked 20 hours. He also wrote: “my eyes are tired and my heart is dead” or “I think I would be happier if I kill myself here.”

While these dramatic cases seem remote and typical of other countries, the karoshi is nothing but a brutal reflection as far as the capitalist mentality, which mixes meritocracy with the most strenuous competition to be (or appear) / us be (to seem) more worthy to occupy a place in this world.

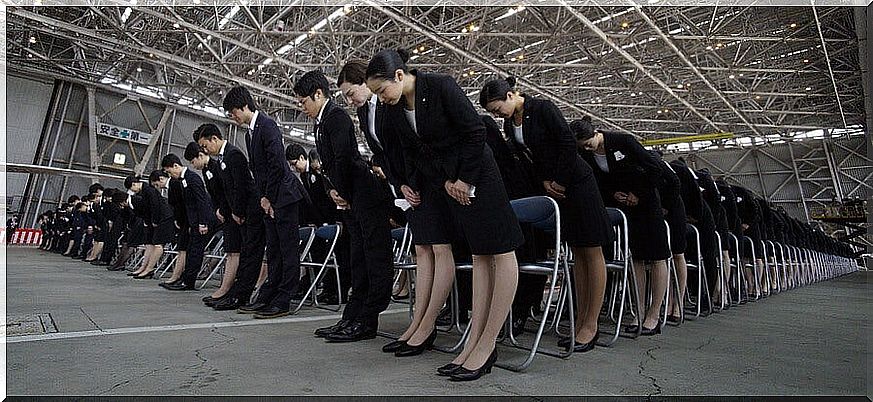

Karoshi : work in Japan is a matter of honor

On average, a Japanese employee works 2,070 hours a year. Overwork is the cause of the death of about 200 people a year, from heart attack, stroke or suicide. Additionally, there are many serious health problems that result from working non-stop.

This way of looking at work is one of the legacies of the golden age of Japanese economics in the 1980s. Hideo Hasegawa, a professor at the University and a former Toshiba executive, expresses this idea of work perfectly: “When you are responsible for a project, it must be carried out, under any conditions. It does not matter how many hours we work. Otherwise it is unprofessional “,

The reputation for good work that the Japanese obsessively pursue is not a myth. Many employees feel guilty about leaving their company on vacation, fearing that they will be perceived as “the one who rests by letting others work in their place. “

There are cases of employees who do not want to return home too early for fear of what they will tell their neighbors or relatives about their alleged lack of seriousness. In addition, you try to go for a drink with your co-workers to promote the corporate culture.

But this hard work is not very lucrative. In fact, their productivity is often described as low by outside observers who believe that this partly explains the competitiveness deficiencies of companies in the archipelago.

In the long term, this way of working is not only uncompetitive in commercial terms, but also poses a risk to the health of the population, and can lead to the collapse of medical resources. In fact, depression and suicide as a consequence already appear as the main challenges to address in a society obsessed with accumulating hours of work.

How is it possible for a person to reach the state of karoshi

The problem is that burnout remains a “fuzzy concept” that, for the moment, does not appear in any of the major international classifications of mental disorders. People can be in a hospital with symptoms associated with exhaustion: extreme tiredness, emotional exhaustion, or depersonalization with insensitivity towards others without identifying the symptoms with a karoshi picture .

There is no clear diagnosis for these symptoms, nor are there any parameters to know if the limit of what can be worked without risking health has been reached. This lack of mental health awareness, increasingly abusive work practices, and a technology-transformed job market are pushing all boundaries of dedication to work.

The fear of unemployment and being left out of the system leads people to believe that working at any time is a good option, when in reality intellectual capacities are reduced and the consequences for health can be irreversible, with a greater risk of falling into addictions of all kinds.

The karoshi, therefore, would resemble a “chronic stress” that can no longer resist, patients no longer have the ability to stand and fall into depression. The term burnout however is much more socially accepted than depression in Japan, as extreme exhaustion is considered almost a “title of glory”, while depression is clearly less “glorious”: it is perceived as a form of weakness.

But this phenomenon is not restricted to the Japanese. Americans have even given it a name: “workalcoholism.” This dependence on work also occurs in the Old Continent. In Spain, more than 12% of the population suffers from this disease and 8% work more than 12 hours a day. In Switzerland, one in seven active people admits to having been diagnosed with depression.

Measures to combat karoshi

To fight the phenomenon, mentality must change. For starters, Japanese entrepreneurs will have to shake off the false idea that long working hours are essential. They would have to learn from European countries like Germany, France or Sweden and move towards a business model that promotes shorter hours.

The Government of Japan is already acting through legal reforms and more scrupulous administrative supervision, correctly using the authority of the State to end long hours. He approved a reform that allows companies to stop paying overtime to workers who earn more than 80,000 euros a year, who are the most likely to burn out.

In addition, the state wants to impose a minimum of 5 days of vacation on Japanese employees to fight against overinvestment in work, detrimental to employee health and business productivity. In the Land of the Rising Sun, workers are rewarded with 20 paid vacation days per year, if they are at least six and a half years old. However, employees take less than half of these vacations.

The new law does not apply to part-time employees, but only to employees who are entitled to at least 10 days of paid annual leave. In fact, it would apply when there is a real health risk of an accident at work or death due to fatigue.

Finally, citizens should also be involved in the transformation of workplaces, making their voice heard before employers and before the Government, and demanding those feasible working conditions that relieve them of pressure.

As citizens, it is also necessary to reflect and consider whether, with our excessive demand for service, we will not be promoting the hardening of the working conditions of workers.