Altruism Is The Only Reason That Can Rescue Our Hope

Abigail Marsh tells us in one of her lectures on altruism how when she was 19 years old, when she returned home, she spun her car to avoid a dog and ended up invading the express lane of the freeway for cars traveling in the opposite direction. Then his stopped and he thought he was going to die.

However, an unknown person who witnessed the scene did not hesitate to stop her car on the shoulder, cross the highway and rescue her from its blockage. The stranger managed to start the car and get Abigail to safety. Finally, when he was sure he was okay, the stranger left and has never seen him again.

The question is why, why would someone risk his life to save that of another person who knows nothing. Why do some people do it all the time, some do it occasionally, some exceptionally, and some never do it, even though the cost of the help response is minimal for them.

Different people who had donated kidneys to other people who did not know anything were asked what they thought differentiated them from others. They claimed nothing. That in fact the answer to their altruism was not in them, since they had simply done it for the other. Somehow they had included this anonymous and unknown recipient in the same circle as his self, they had confused him. Hence, for them it was a natural act, or would we not donate a kidney to ourselves?

This is also how we are. Remembering this, we accumulate arguments to face that mirror in which we can see ourselves distorted by the fact that its glass only reflects our dark side, through the galloping frequency with which we are spectators of acts of cruelty that open and close newscasts. However, we are also like those people who thought that others were not the least, that they were equal to more than themselves.

Altruism comes to the rescue

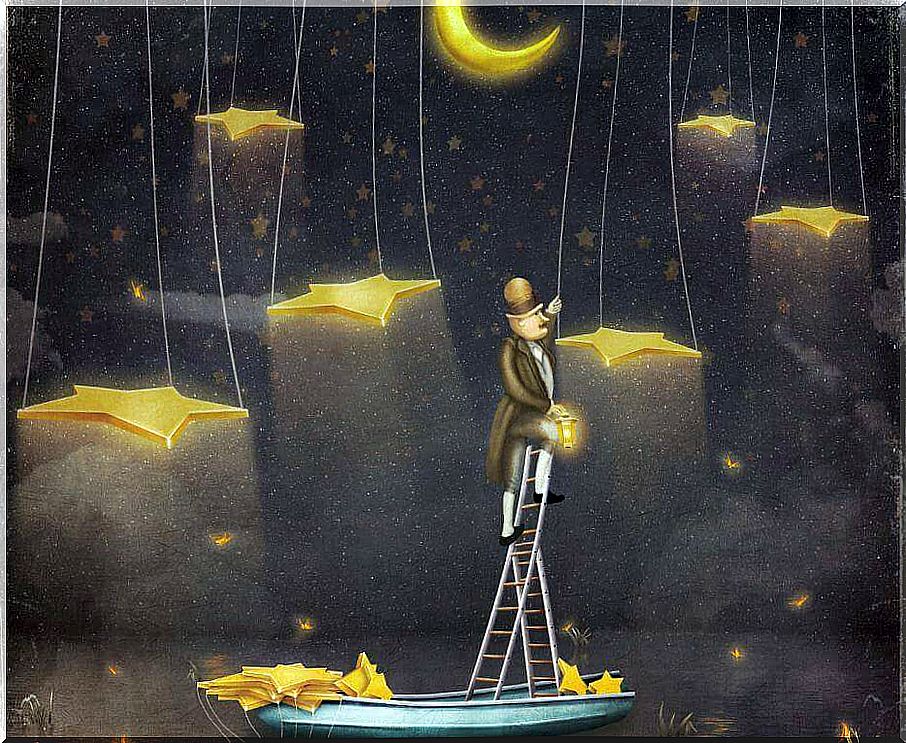

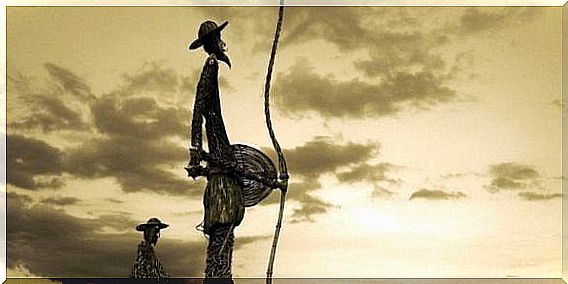

On June 3, while half the world was aware of what happened with 22 people running after a ball, the knight of the sad figure, Don Quixote de la Mancha, was resurrected. He did it in London, crossing the Thames, with a scooter instead of a spear. He came back to life for a few moments, in the person of Ignacio Echeverría and the rest of the brave people who that day decided that their duty was greater than fear.

Like the baker who sheltered two Brazilian students in his establishment, then went out onto the street carrying two wooden boxes as weapons. One threw it at the first terrorist he encountered, taking advantage of his bewilderment to hit him with the other and giving a nearby policeman time to shoot him.

Or the taxi driver who ran out of his taxi to protect the life of a woman who was, and never better said, between a rock and a hard place. Stories of anonymous heroes who will inevitably be forgotten and who somehow rescue humanity from that tragedy and give us hope.

Altruism and psychopathy

If we understand that psychopathy is at the other extreme of altruism, understanding what characterizes psychopaths can help us understand what happens. Studies tell us that these types of people who seem insensitive to the suffering of others would have three characteristics.

- More insensitive to the signals of people who are in danger, such as the facial expression of fear. Usually signs of distress are a strong inspiration for altruism and compassion.

- They have an underactive amygdala. That is, part of your emotional nervous system is not activated with the same intensity as in other people.

- Lastly, the tonsils of psychopaths are smaller than average by about 18% or 20%.

Now the questions are: Could unsurpassed altruism, which is the opposite of psychopathy in terms of compassion and a desire to help other people, emerge from a brain that is also the opposite of psychopathy? Some kind of antipsicopathic brain, better able to recognize other people’s fear, with an amygdala more reactive to this expression and perhaps larger than normal?

Altruism, the best reason for hope

Seems that if. That altruistic people also have certain characteristics in their architecture and brain dynamics that identify them. They have a greater sensitivity to expressions of fear and, therefore, to demands for help. In addition, they have an amygdala that works more and also has more resources to do so: it is larger and is made up of more cells.

Abigail says that what truly characterizes altruists and makes them so special is that they do not have a differentiated center in which they and others are, but that others would be part of that center. Thus, this distinction would prevent selfishness or, rather, extend it to everyone.

Perhaps, as Unamuno said, in times of despair the only thing that can save us is a madness like the Quixotic. A challenge to common sense to commit ourselves to the most worthy causes, which are the lost causes. Thus, perhaps the probabilities of success should not be those that decide in which battles we should use our forces, but rather it should be the justice that those same battles contain that gives priority to some and subtracts them from others.

In this way, the right thing is heroic because someone is willing to do what many others do not, when we all should. Heroes who die like Ignacio died give death a meaning. They leave a life that remains in others and gives a meaning to the hope that struggles to survive crushed by all acts of evil. A hope that is ours and that deep down we are all called to feed so as not to relegate the best part of our nature to oblivion.